Tariq Saeedi

Gaziantep (Turkey), 18 May 2016 / Ashgabat (Turkmenistan), 22 May 2016 — Here are a couple of stanzas from ‘Home,’ a powerful and moving poem by Ms. Warsan Shire, a Kenyan-born Somali poet and writer:

no one leaves home unless

home is the mouth of a shark

you only run for the border

when you see the whole city running as well

[…]

i want to go home,

but home is the mouth of a shark

home is the barrel of the gun

and no one would leave home

unless home chased you to the shore

* * *

About half of the population of Syria – nearly 11 million people – is either internally displaced or refugee. Turkey is host to some 3 million of them.

A group of journalists, at the invitation of the Turkish government, recently visited Gaziantep, the Turkish province bordering Syria that is looking after about 350000 Syrians who have fled their homes in search of safety and peace.

Turkey doesn’t describe them as refugees. “We don’t call them refugees; they are our brothers, our guests. They have equal rights and obligations with the Turkish citizens,” said Halil Uyumaz, the deputy governor of Gaziantep.

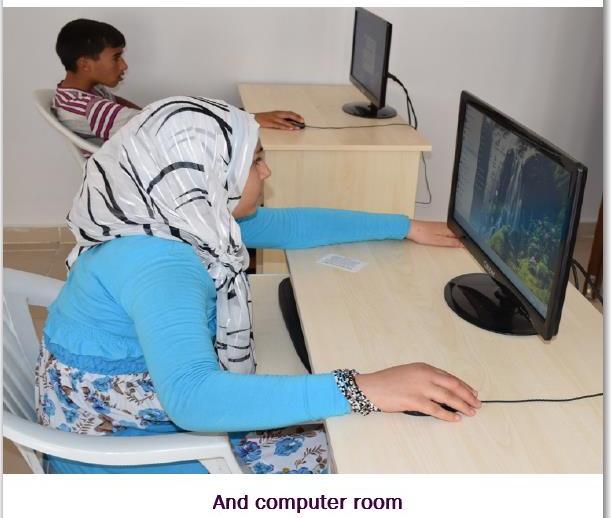

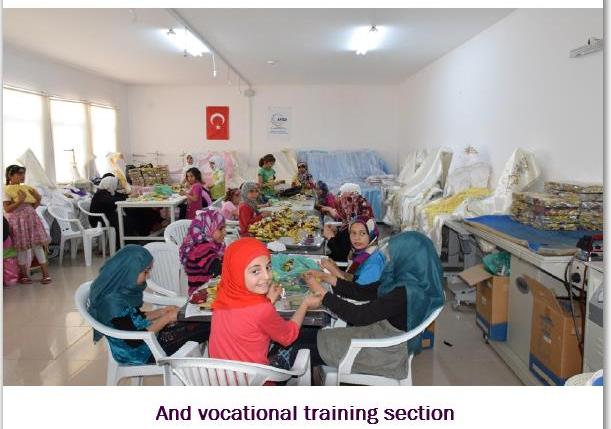

He said that each guest is guaranteed accommodation, food, healthcare services, education, vocational training and place of worship. The stipend is equivalent to USD 200-300 and 75% of all expenses are being met by the Turkish government from its own budget, he said.

A day earlier in Ankara, Fatih Ozer, the head of the response department of AFAD – an acronym for the disaster and emergency management authority of Turkey, told that the country had spent USD 20 billion so far in taking care of the guests and will continue to maintain the open doors policy for the Syrians seeking shelter in Turkey.

When asked whether more refugees were expected to cross into Turkey in the near future, he said, “There is no end in sight.”

* * *

Even though it is highly admirable to call them guests or brothers to maintain whatever little dignity is left in their personal situation, these unfortunate masses must be called refugees to scratch and awaken the numbed world conscience.

As soon as they step across the borders, they are just refugees i.e. people seeking refuge. They must be called refugees because the powers that have jointly caused their predicament are the same that are busily preventing any solutions for their return home.

* * *

Despair

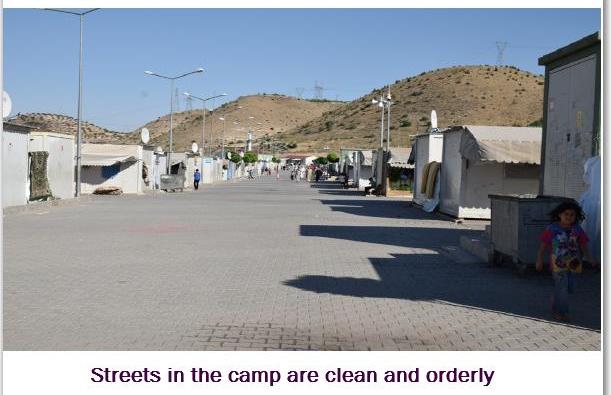

We spent about half a day at Nizip Container Kent, an orderly and well maintained temporary camp for the refugees. It is just next to a tented village, and the total population of the entire camp is about 5000, of which nearly half are children.

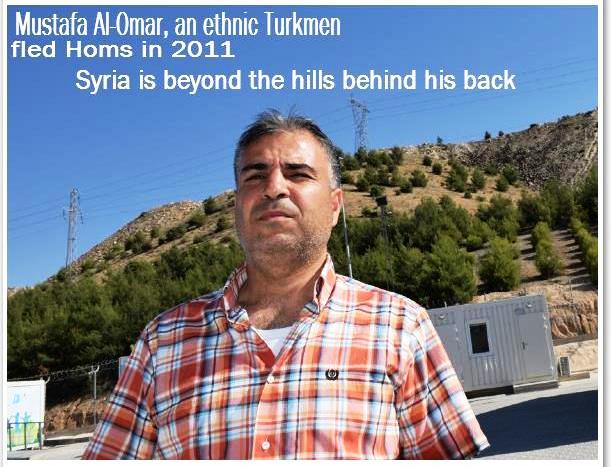

I spoke to several of the refugees. Only one of them, Mustafa Al-Omar, an ethnic Turkmen from Homs, agreed to be identified and photographed. Two others just gave their first names but declined to be photographed. The rest didn’t even tell their names though they also answered some questions. The main concern here is that most of them still have relatives in Syria and they don’t want any harm to come to them.

Mustafa Al-Omar, 39, was an English language teacher in Homs. He didn’t mince any words in the conversation.

“How did the problem start in Homs,” I asked.

He said, “We told the regime we want reforms but instead of reforms they sent soldiers, the soldiers and tanks, and the protests quickly turned violent.”

“Didn’t Assad want to listen to the peaceful protestors?”

“He didn’t differentiate between peaceful protestors and militants. When the soldiers came, they killed everyone.”

“Were the people always against Assad?”

“People just wanted reforms. In the beginning no one was against Assad. Step by step, it became militant.”

“What was the situation like when you left Homs?”

“When we fled from Homs in 2011, the death toll in the town had already exceeded 9000.”

“When you left Homs, did you head straight to Turkey?”

“No, when they bombed our houses, we went to the countryside. On 1 September 2012, my brother, who was 3rd year engineering student, was killed by aerial bombing, and that is when we decided to leave Syria.”

“Was it easy to travel to Turkey?”

“We were besieged by the Assad troops; no food, no medicines.”

“Were most people in this camp forced by similar situations to flee Syria?”

“Kidnapping and killing was rampant. There was no telling when it would be your turn to be kidnapped and killed, that is why most people left their homes.”

“Has anyone thought of returning home so far?”

“About fifty percent in this camp were thinking of returning to Syria but after the start of the Russian strikes they changed their mind.”

“What are the main ethnic groups in this camp?”

“There are about 5000 persons in this camp and they are mainly Arabs, Turkmens, Kurds and Cherkez.”

“How many children do you have?”

“I have three children, all boys; one of them was born here in the camp.”

“Why did the situation turn worse when you were thinking of returning to Syria?”

“I don’t know why things went bad, maybe Iran, maybe Iran told him not to introduce any reforms.”

“What kind of atrocities did your relatives suffer?”

“My two brothers were imprisoned simply for joining a peaceful protest; we paid heavy bribes to get them free. My two uncles went to prison; one of them spent 10 months there. He says that the lightest torture he and other prisoners were subjected to was electric shocks. He says that rape, multiple times a day, and painful sex with intent to injure were used as a method of intimidation.

My uncle served long periods in isolation with no food.”

“What do you think why this conflict is not coming to an end?”

“The west doesn’t this conflict to end.”

“How do you feel about the whole situation?”

“I have lost faith in my future. I am just worried about the future of my children.”

“Will you return if a solution is found where Assad remains in power?”

“The Syrian people will suffer anywhere rather than return to Syria and live under the Assad regime. They are all criminals, Assad and his regime.”

Another person I talked to gave his first name as Mustafa. He is an ethnic Kurd, also from Homs. He came to the camp about three years ago.

“Why did you leave your home,” I asked.

He said, “When disturbance started, I moved to Aleppo. When bombs started shattering windows in Aleppo, I fled to Turkey.”

“What are the reasons for this unrest and bloodshed in Syria?”

“The situation is very complex. USA, Russia, Iran and Israel have their own interests. Israel, by hoping to split Syria into three countries, could be expecting to safeguard its own borders. Russia knows that its base in Syria will go if Assad goes. USA remain ambivalent about the Syrian question. Iran is interfering in Syria, Egypt, and Lebanon for a number of reasons.”

I also spoke to Mohammad, an ethnic Arab from Syria.

I asked him as to why did he leave Syria.

He said, “They killed my nephew and wanted to recruit my sons into the army.”

I asked him if he has any hope for peaceful return to the homeland. He said, “I don’t have any hopes for peace.”

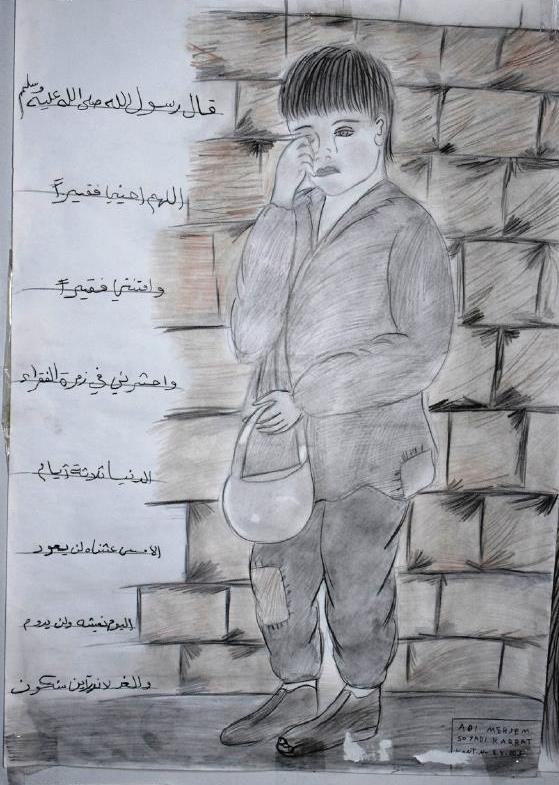

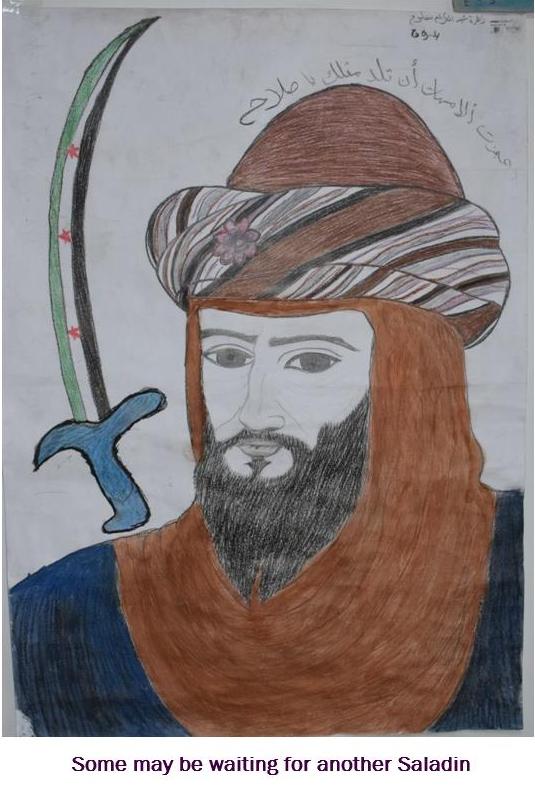

Expression of despair through art

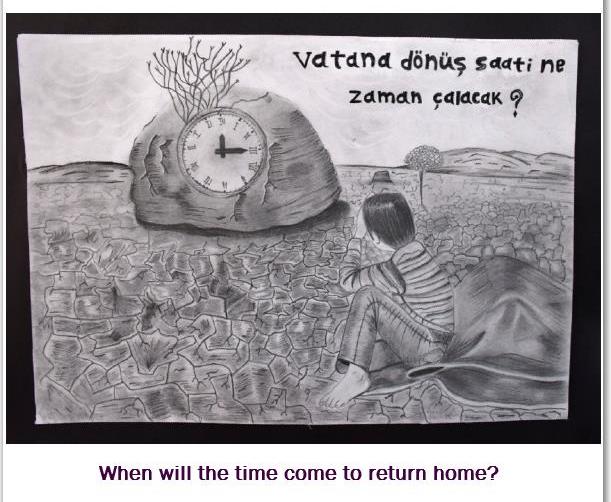

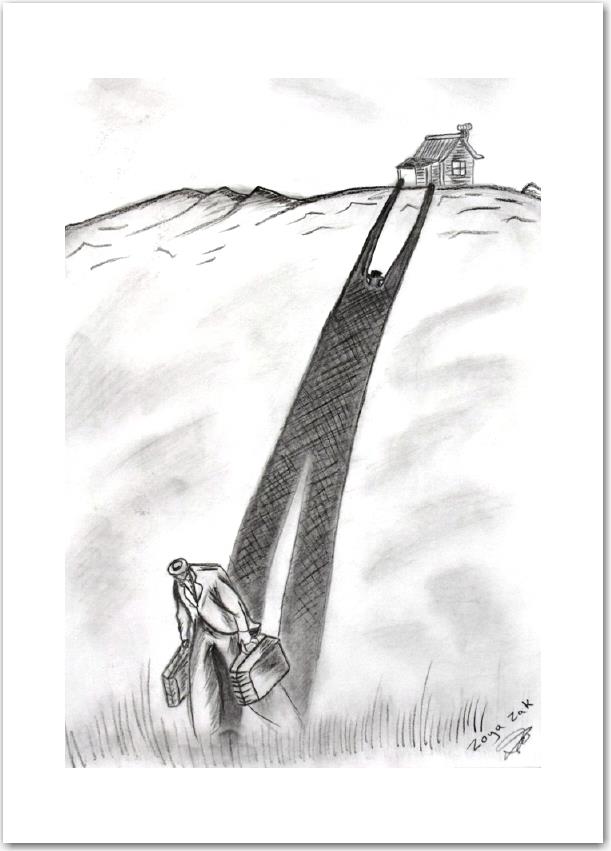

A room at the Nizip Container Kent, which is part of the Nizip-2 camp, is dedicated to the art work of the refugee children.

A child asks a simple question that no one can answer — When will the time come to return home?

The heart-rending drawing by teenage Zoya Zak shows a departing man but his shadow doesn’t want to let go of the home.

Cautious hope

The efforts of the Turkish government are focused on the children, mainly their education, healthcare and general upbringing. In the Nizip-2 camp there are 2507 children. According to their age, they go to the kindergarten, the middle school or the high school. The education is based on the Syrian system. There are 95 Syrian and 17 Turkish teachers. The medium of instruction is Arabic, which is the mother tongue of almost all the children in the camp. In addition they are taught the Turkish and English languages.

Depending on the size of the family, each family unit is given one or two containers. The covered area of the container is 21 square meters, divided into three sections. Electricity and drainage system are connected to each container. There is dish antenna for satellite TV reception and there is also split or window-type air conditioner for each container.

There is cautious hope in the sense that the lives of the refugees in Turkey are in no immediate danger and their food and shelter is guaranteed.

The scars of trauma will remain there even when the pain subsides. Halil Uyumaz, the deputy governor of Gaziantep said, “They are good people. They were damaged psychologically but now they are in much better shape.”

The proportion between the rates of birth and death is a fair indicator to judge his words. Since the start of the camp some 5 years ago, there have been 37 deaths and 340 births.

Children, the born optimists

Children are born optimists. Half of the population of the Nizip-2 camp is composed of children. The pain is still in their eyes but they dare to smile.

Waiting for world conscience to awaken

Syria is a manmade tragedy, a long series of war crimes. Behind the fancy words from all sides, there are foulest ambitions. The odious lake of pus is boiling under the woefully inadequate cover of civility.

The children of Syria are waiting for the world conscience to awaken.

<<<>>>