Tariq Saeedi

The UNDP Turkmenistan arranged a briefing for the media, civil society, and UN system agencies on 9 December 2019 to unveil the global Human Development Report (HDR) 2019.

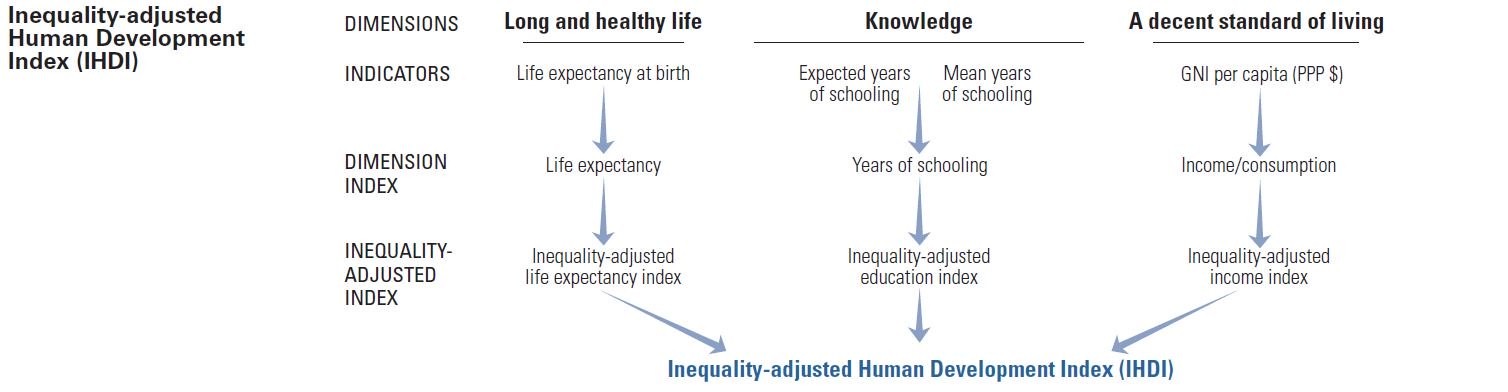

A significant feature of the HDR 2019 is that in addition to HDI (Human Development Index) it provides the IHDI (Inequality-Adjusted Human Development Index) for the depth perception. This is useful for the policymakers and decision-makers.

The HDI is a statistical tool used to measure a country’s overall achievement in its social and economic dimensions. It takes into account the health of the people, the level of their education, and their standard of living. In other words, it goes beyond the numbers and tries to measure the upward or downward trends in the quality of life of the people. Developed by the Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Haq in 1990, HDI is now recognized as a standard instrument by all the countries and international and regional development institutions.

Here is how the ‘Human Development Reports’ section of the website of UNDP defines IHDI:

The IHDI combines a country’s average achievements in health, education and income with how those achievements are distributed among country’s population by “discounting” each dimension’s average value according to its level of inequality. Thus, the IHDI is distribution-sensitive average level of human development. Two countries with different distributions of achievements can have the same average HDI value. Under perfect equality the IHDI is equal to the HDI, but falls below the HDI when inequality rises.

The difference between the IHDI and HDI is the human development cost of inequality, also termed – the overall loss to human development due to inequality. The IHDI allows a direct link to inequalities in dimensions, it can inform policies towards inequality reduction, and leads to better understanding of inequalities across population and their contribution to the overall human development cost. A recent measure of inequality in the HDI, the Coefficient of human inequality, is calculated as an unweighted average of inequality across three dimensions.

The alarming finding, according to the IHDI 2019, is that 20 per cent of human development progress was lost through inequalities in 2018.

* * *

The UNDP press release on HDR 2019 dealing with the Eastern Europe and Central Asia region identifies the uneven access to technology and education and climate-related factors as the areas of concern.

The HDR 2019 notes:

Historically more equal, region now faces unstable labour markets and social exclusion Europe and Central Asia experienced the lowest overall losses in human development from inequality as measured by the Inequality Adjusted Human Development Index, indicating that inequality here, while very present, is less pronounced on average than in other regions. The region has also made notable progress in expanding tertiary education, closing in on developed countries.

Nevertheless, the report’s findings support the conclusions of the 2016 regional HDR, which stated that labour market inequalities and exclusion lie at the heart of the region’s inequality challenges and are driving the emigration that is aggravating depopulation trends in much of the region.

Labour market exclusion in the region is important both in terms of the availability of decent jobs, and because access to social protection is often linked to formal labour market participation. Those not in decent employment face much higher risks of poverty, vulnerability, and exclusion from social services and social protection.

Survey data also indicates public concern about the quality of governance, particularly regarding corruption and inequality before the law. Such perceptions may reflect deeper concerns about inequalities that are not captured in official socioeconomic data.

Human Development Report 2019 – Beyond income, beyond averages, beyond today: Inequalities in human development in the 21st century

download link http://hdr.undp.org/en/2019-report

* * *

Human Development Report (HDR) with its HDI and IHDI is a useful instrument but not a complete toolbox.

By bracketing Central Asia with Eastern Europe it drifts away from relevance.

Some of the challenges facing Central Asia are global in nature but local in texture; some are just a temporary phenomenon.

For instance, access to education is not the problem in Central Asia. Up to secondary school, the education is mandatory and free. The problem is that the educational system in the region, as in most of the world, is not able to prepare the students to cope with a fast-changing world. —– The babies learn to take selfies before they learn to say mama.

There is the need to revisit the entire concept of education as we know it today. It is a task every country and every region must tackle in their own way, drawing from the contemporary experience.

Another problem of universal nature with localized consequences is the Internet habits of the people. —– How much time do we spend on liking the pictures of cute babies and derpy doggos, how many funny videos and jokes we share every day, what is the volume of gossip we generate and re-circulate, how many times a day we take sides in silly debates, etc.

These Internet habits are addictive and there is still no technique to measure their impact on the society as a productive and inclusive organism.

The volatility of markets, coupled with the consumption habits, is yet another issue of global nature with local hues. Because of this, the people in the low-paying jobs keep drifting above or below the poverty line seasonally.

There are gaps: The gap between the education system we have and the education system we need; the gap between the job opportunities and the availability of the youth with those job skills; the gap between the aspirations for gender equality and the capacity to enforce the gender equality; the gap between the actual requirements of the people and the desires that are born because of the use of the social media; the gap between the real priorities and perceived priorities, etc. —– The gap between who we are and who we believe we are.

There are patches of awareness here and there, and the governments in Central Asia are in the process of coming together to deal with the issues that have descended on them. For example, the joint statement issued at the end of the consultative summit of the heads of Central Asian states, recently concluded in Tashkent, expressed the desire to work jointly in every area of life and economy.

Inequality could be on the rise but it is still not the main challenge in Central Asia. The real problem is the need for justifiable and flexible repurposing of the human and material resources.

The Human Development Report is not a criticism of the performance of any country. It is not a report card. The real purpose of HDR is to spotlight the areas where more can be done. As to how can that be done is beyond the scope of HDR although useful pointers are part of the package.

As long as we cannot fully define every problem we face, we cannot find every solution we need.

Central Asia should treat the Human Development Report 2019 as a timely reminder. /// nCa, 10 December 2019