nCa Analysis

France is burning. We sincerely hope the flames would be quenched soonest but the bitter fact is that the embers would keep smouldering.

President Macron decided to raise the age of retirement from 62 to 64 and that caused a wave of resentment.

Soon after, Macron forced the bill through without putting it to a parliamentary vote first, using an emergency presidential decree, before it got to a National Assembly vote in the afternoon. This turned the resentment to anger.

A poll by Reuters notes that more than 70% of the public oppose the move.

Although there can be many reasons to dislike Macron, the increase in the age of retirement is not one of them. He cannot do anything against the force of economy. His fault, if any, is forcing the bill on the force of a presidential decree rather than letting it run through the parliament.

The increase in the age of retirement is the byproduct of the increasing disfigurement of the Population Pyramid, a phenomenon catching up with several other countries.

In simple, perhaps even simplistic terms, the population pyramid should be thin at the top and broad at the base i.e. the number of senior citizens should be lot less than the number of able-bodied people who contribute to the economy.

Some call it the curse of prosperity. —– All of the 35 countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are facing this challenge.

The increased life expectancy that is the result of better nutrition and healthcare has added to the number of years the people may spend after retirement. For example, life expectancy at birth in the UK has risen from 75 to 82 over the past 30 years.

Since they live longer, it is becoming progressively difficult to pay pensions and provide other benefits to them. The number of pensioners is increasing while the resources to serve them are either stagnant or shrinking.

The primary reason is that proportionally there are fewer able bodied people to generate economic benefits to serve the entire population including the pensioners.

* * *

First, let’s try to understand the Population Pyramid.

For this, we would refer extensively to a meticulously compiled report by Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser, available at the website of ‘Our World in Data.’ The title of the report is: Age Structure

Our World in Data — Age Structure by Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser

This section of our report is based entirely on the work of Ritchie and Roser.

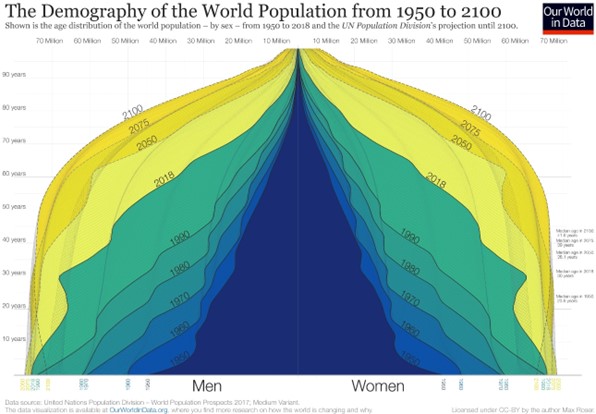

The starting (also startling) fact is that the population of the planet was 2.5 billion in 1950 and it would exceed 10.4 billion by the end of this century. This visualization of the population pyramid makes it possible to understand this enormous global transformation.

Population pyramids visualize the demographic structure of a population. The width represents the size of the population of a given age; women on the right and men on the left. The bottom layer represents the number of newborns and above it, you find the numbers of older cohorts. Represented in this way the population structure of societies with high mortality rates resembled a pyramid – this is how this famous type of visualization got its name.

In the darkest blue, you see the pyramid that represents the structure of the world population in 1950. Two factors are responsible for the pyramid shape in 1950: An increasing number of births broadened the base layer of the population pyramid and a continuously-high risk of death throughout life is evident by the pyramid narrowing towards the top. There were many newborns relative to the number of people at older ages.

The narrowing of the pyramid just above the base is testimony to the fact that more than 1 in 5 children born in 1950 died before they reached the age of five.

Through shades of blue and green the same visualization shows the population structure over the last decades up to 2018. You see that in each subsequent decade the population pyramid was larger than before – in each decade more people of all ages were added to the world population.

If you look at the green pyramid for 2018 you see that the narrowing above the base is much less strong than back in 1950; the child mortality rate fell from 1-in-5 in 1950 to fewer than 1-in-20 today.

In comparing 1950 and 2018 we see that the number of children born has increased – 97 million in 1950 to 143 million today – and that the mortality of children decreased at the same time. If you now compare the base of the pyramid in 2018 with the projection for 2100 you see that the coming decades will not resemble the past: According to the projections there will be fewer children born at the end of this century than today. The base of the future population structure is narrower.

We are at a turning point in global population history. Between 1950 and today, it was a widening of the entire pyramid – an increase in the number of children – that was responsible for the increase of the world population. From now on is not a widening of the base, but a ‘fill up’ of the population above the base: the number of children will barely increase and then start to decline, but the number of people of working age and old age will increase very substantially. As global health is improving and mortality is falling, the people alive today are expected to live longer than any generation before us.

At a country level “peak child” is often followed by a time in which the country benefits from a “demographic dividend” when the proportion of the dependent young generation falls and the share of the population of working age increases.3

This is now happening on a global scale. For every child younger than 15 there were 1.7 people of working age (15 to 64) in 1950; today there are 2.6; and by the end of the century, there will be 3.6.4

Richer countries have benefited from this transition in the last decades and are now facing the demographic problem of an increasingly larger share of retired people who are not part of the labor market. In the coming decades, it will be the poorer countries that can benefit from this demographic dividend.

The change from 1950 to today and the projections to 2100 show a world population that is becoming healthier. When the top of the pyramid becomes wider and looks less like a pyramid and instead becomes more box-shaped, the population lives through younger ages with a very low risk of death and dies at an old age. The demographic structure of a healthy population at the final stage of the demographic transition is the box shape that we see for the entire world in 2100.

With this basic explanation of the Population Pyramid in mind, the next thing to understand is the Median Age.

* * *

This section of our report is also based entirely on the work of Ritchie and Roser. However, we have picked the data from their vast report to create direct relevance for Central Asia.

The median age provides an important single indicator of the age distribution of a population. It provides the age ‘midpoint’ of a population; there are the same number of people who are older than the median age as there are younger than it.

The global average median age was 30 years in 2021 – half of the world population were older than 30 years, and half were younger. Japan had one of the highest median ages at 48.4 years. One of the youngest was Niger at 14.5 years.

Overall we see that higher-income countries across North America, Europe, and East Asia tend to have a higher median age.

On the other hand, Central Asia is a considerably young region.

| Country | Median Age (years) |

| Kazakhstan | 29.5 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 23.7 |

| Tajikistan | 21.5 |

| Turkmenistan | 25.8 |

| Uzbekistan | 26.6 |

With the concept of Population Pyramid and Media Age fresh in our mind, the next thing to understand is the division of the population into age groups.

It is common in demography to split the population into three broad age groups:

- children and young adolescents (under 15 years old)

- the working-age population (15-64 years) and

- the elderly population (65 years and older)

A large share of the population in the working-age bracket is seen as essential to maintain economic and social stability and progress. And since a smaller share of the younger and older population is typically working these two groups are seen as ‘dependents’ in demographic descriptions.

A large fraction of economically ‘dependents,’ relative to those in the working-age bracket, can have negative impacts for labour productivity, capital formation, and savings rates.

Demographers express the share of the dependent age-groups using a metric called the ‘age dependency ratio’. This measures the ratio between ‘dependents’ (the sum of young and old) to the working-age population (aged 15 to 64 years old).

It’s given as the number of dependents per 100 people of working-age. A value of 100% means that the number of dependents was exactly the same as the number of people in the working-age bracket. A higher number means there are more ‘dependents’ relative to the working-age population; a lower number means fewer.

We see big differences across the world. The majority of countries have a ‘dependent’ population that is 50-60% the size of its working-age population. The ratio is much higher across many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa: Niger and Mali, for example, have a larger dependent population than they have working-age populations. As we see in the next section, this is the result of having very young populations.

Here too, Central Asia is in the safe range.

| Country | Age dependency ratio, 2021 |

| Kazakhstan | 59.96% |

| Kyrgyzstan | 63.53% |

| Tajikistan | 65.94% |

| Turkmenistan | 56.57% |

| Uzbekistan | 53.97% |

Now we come to the youth dependency ratio.

The young dependency ratio is high across Sub-Saharan Africa in particular. Some countries in this region have close to the same number of young people as they have working-age population. The youth dependency ratio is much lower across higher income countries since fertility rates tend to be much lower there.

Central Asia fares better than a large number of countries because even though the youth are dependent now, they are preparing to join the productive segment of the population. Investment in them is investment in the future.

| Country | Youth dependency ratio, 2021 |

| Kazakhstan | 47.24% |

| Kyrgyzstan | 56.36% |

| Tajikistan | 60.42% |

| Turkmenistan | 48.8% |

| Uzbekistan | 46.3% |

This brings us to the last element for the completion of our concept i.e. the old-age dependency ratio.

The old-age dependency ratio is almost a mirror image. Higher-income countries – particularly across Europe, North America and East Asia – have the highest dependency ratios.

In plain language, this is the percentage of the population that is over the age of 65, is eligible for the pension and other retirement benefits, and is mostly unable to contribute fully to the economic activity.

Central Asia is better placed than most countries around the world.

| Country | Old-age dependency ratio, 2021 |

| Kazakhstan | 12.72% |

| Kyrgyzstan | 7.17% |

| Tajikistan | 5.51% |

| Turkmenistan | 7.69% |

| Uzbekistan | 7.67% |

* * *

These are reassuring indicators. Central Asia is at no risk to face the pension crisis. Nevertheless, this is no reason to be complacent. There are two separate sets of measures that must be put into place as early as possible. /// nCa, 28 March 2023

To be continued . . .