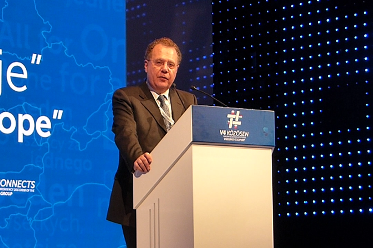

David P. Goldman , Deputy Editor of Asia Times, Washington Fellow of the Claremont Institute

According to the World Bank, China’s real per capita GDP rose from $404 in 1979—the year Deng Xiaoping opened the economy to private enterprise—to $11,560 in 2022 in constant 2015 U.S. dollars. It jumped five-fold since 2001. By contrast, India’s real per capita GDP rose from $373 in 1979 to just $2,085 in 2022. By comparison, you can see what a success story China has been, one unique in economic activity.

This is not to say Deng’s trajectory is still at play. Deng Xiaoping’s economy, which turned subsistence farmers into semi-skilled industrial workers, surely has peaked. The great migration from country to city is slowing, and China’s workforce is slowly shrinking.

But China is building a new digital economy powered by AI and high-speed broadband, with 2.3 million of the world’s 3 million 5G base stations and download speeds double ours. It has automated ports that can empty a container ship in 45 minutes rather than the 48 hours required at our port of Long Beach. It’s also automated mines where no worker goes underground, factories controlled by AI, and warehouses in which robots do the sorting and packaging.

Most of all, nearly two-thirds of Chinese citizens have an education beyond high school, compared to just 3 percent who had one in 1979. China graduates more engineers than the rest of the world combined, and Chinese universities teach at world standards.

China has also extended its economic reach to developing economies. It now exports more to the Global South than to developed markets, doubling its exports to ASEAN and tripling its exports to Central Asia after 2020. It builds broadband, railroads, and ports from Africa to South America, promoting a permanent market for its exports.

China’s new digital economy is in early days, to be sure, and a lot can go wrong. But some things are going right. China overtook Japan as the world’s largest auto exporter this year, thanks in part to Tesla‘s mega-plant in Shanghai. China now makes the 21st century equivalent of the Model T in the form of EVs with a $10,000 price tag.

Demographic doomsayers are simply wrong. A declining workforce doesn’t necessarily mean a declining economy. South Korea quintupled industrial production between 1990 and 2010 while its factory workforce fell by a fifth. It moved up the value-added chain to make high-end electronics, cars and computer chips. Higher education transformed South Korea from a cheap-labor venue to a high-tech contender.

China is on the same path. In 1994, just before the “Asian tigers” took off, Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman derided “the myth of Asia’s miracle,” claiming that the “tigers” had exhausted their reserves of cheap labor. He missed the jump in productivity to come, just as “peak China” pundits do today.

China is determined to lead the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The Chinese telecom giant Huawei claims to have 6,000 contracts to build enterprise 5G networks to support factory AI applications, as I reported in a March commentary for Newsweek. Huawei offers a Cloud-based AI system to enable firms to create their own applications. China is now the world’s largest market for industrial robots. If what we have already seen in the EV sector propagates through the rest of the economy, China will gain an insurmountable lead in industry. U.S. tech controls don’t have much impact. Industrial applications of AI run well enough on the older chips that China makes at home. Without access to the newest chips, Huawei can’t sell a competitive 5G smartphone, but its AI apps can run factories, ports, and mines.

China has made missteps, to be sure. Last year’s COVID lockdowns in Chinese cities were a blunder that continues to depress consumer spending. Beijing’s crackdown on China’s top tech companies has left China’s stock market lagging the rest of the world, and raises the cost of capital for China’s emerging tech companies. China’s universities are graduating STEM majors faster than the tech sector can hire them, and youth unemployment is at a record 21 percent. In the long run, that’s a high-class problem to have. In the short run, it’s painful.

Predictions of China’s imminent collapse, though, are as misguided now as they were 20 years ago. China’s debt-to-GDP ratio is 3:1, a bit higher than America’s 2.5:1 ratio, but much lower than 4:1 in Japan. The Chinese sovereign borrows 10-year money at 2.6 percent, compared to 4.1 percent for the U.S. China’s local governments carry RMB about $5 trillion in debt, but they have almost $30 trillion in assets behind it.

We can’t afford to get the China story wrong again. China may succeed or fail in its high-tech transformation, but waiting for China to crash isn’t a policy. We need a crash program to rebuild industry and regain our technological edge, on the scale of JFK’s Moonshot or Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative.

David P. Goldman is Deputy Editor of Asia Times and a Washington Fellow of the Claremont Institute. He formerly was global head of debt research at Bank of America.

/// This is cross post from Newsweek — Originally published at https://www.newsweek.com/china-was-worlds-biggest-economic-miracle-it-will-again-opinion-1816249

#China, #miracle, #David_P._Goldman,