Dr. Begench Karayev

Today there are many statements about the supposed beginning of a new “Great Game”, and almost a world war of a hybrid nature. And, in order to better understand the currently put forward hypotheses and forecasts regarding the “Great Game” for the 21st century, it is necessary to delve in more detail into the essence of the events of a century and a half ago.

To be more specific, Kipling’s classic characterization of East-West relations was given four years before the 1893 negotiations between the Afghan Emir Abdur Rahman and the Indian Colonial Secretary Sir Mortimer Durand. As is known, as a result of the negotiations, a 2,640-kilometer and practically unmarked border between Afghanistan and Pakistan was drawn, which was called the “Durand Line”.

Afghanistan by that time had already gone through the trials of the second Anglo-Afghan war of 1878-1880, as a result of which the young emir Yakub Khan was forced to cede part of the border territory of his country to England as a result of the Treaty of Gandamak on May 26, 1879. British General Donald Stewart ceded Kabul to the new emir Abdur Rahman on August 11, 1880, and in April 1881 the withdrawal of British troops from Kandahar province was completed

While the Afghan events were going on, the Geok-Tepe fortress was preparing for the decisive battle, which was called “Tekin’s [Teke’s] Sevastopol” by the famous Russian writer, ethnographer and traveler Evgeniy Markov, who visited these parts in the mid-90s of the 19th century. Before the well-known events of January 1881, the military expedition of General Nikolai Lomakin suffered a major defeat near Geok-Tepe. “The victorious conquest by the Russians of the inaccessible Akhal-Teke oasis, which was a threat and terror to the surrounding states, began, as everyone remembers, of course, with a shameful failure,” wrote E. Markov, commenting on the victory of the Turkmens, who repeatedly repelled the campaign of the Russian army in the second half of the 70s of the 19th century.

According to the notes of E. Markov, when General Mikhail Skobelev began a new expedition in the fall of 1880, “the Persians, neighbors of the Tekins [Tekes], predicted a new failure for the Russians and did not believe in the possibility of defeating this frantic people.” As E. Markov further noted, the Bujnurd Ilkhan Yarmamed Khan, a great friend of the Russians, convinced Colonel Grodekov with the words: “Believe me, I know the Tekins [Tekes] better than you, I have been fighting with them all my life. There are no braver people in the world than this. And now, when their families are in Geok-tepe, and the Tekins have nowhere to go, their courage will increase tenfold!”

The British also carefully monitored Skobelev’s expedition. In particular, the journalist O’Donovan, dressed in the combat attire of a Turkmen horseman, Colonel Stewart, dressed as an Armenian merchant, as well as captains Gill, Buttler and many other unknown participants in the then “Great Game”. They penetrated the Turkmen lands from the southern borders and tried to find out as much as possible both about the advancement of the Russians and about the fighting spirit and potential of the Tekins.

The British also carefully monitored Skobelev’s expedition. In particular, the journalist O’Donovan, dressed in the combat attire of a Turkmen horseman, Colonel Stewart, dressed as an Armenian merchant, as well as captains Gill, Buttler and many other unknown participants in the then “Great Game”. They penetrated the Turkmen lands from the southern borders and tried to find out as much as possible both about the advancement of the Russians and about the fighting spirit and potential of the Tekins.

In this regard, a Russian agent under the cover of a non-staff trade representative in Mashhad, Kerim Khan Nasirbekov, wrote to Colonel Nikolai Grodekov: “The British have their people everywhere. The money they throw around in these parts can seduce a brother. Fear how they pour gold!” He made this conclusion mainly by observing the activities of a British agent under the cover of the consul in Mashhad, General Maclean. Nasirbekov’s warnings were justified. Thus, in Ashgabat, Haji Mamed Hasan was collecting information for British diplomats. The Merv district was entrusted to three agents, of which the main agent permanently resided in Merv. The Russian consulate collected quite detailed information about the main agent: Indian by origin; born in Bandar-Bushir; was educated in London; spoke 7 languages, etc. In Bandar-Bushir he was known under the name Mirza Musa, and now he pretended to be a resident of Khorasan, Meshedi Suleymaniye. In Khiva, similar cases were carried out by Khivan Nur Yagdi, and in Bukhara by Tach Mamed, a native of Kandahar, and Ghulam Riza, an Afghan.

The Russian consuls were not particularly worried about the presence of such a network of British agents in the region, since most of the information transmitted was not true and was gleaned from communications at the bazaar with visiting merchants. The travel of professional British military personnel to border areas was a cause for concern. One of the first was Colonel Gerard, who rode along the border in 1885, followed by Major Bellier (February 1890) and General McLean (November 1890). In contrast to rumors obtained by local agents, resident officers received more reliable information. In particular, Bellier, having traveled along the entire Russian-Afghan border, collected information about the number, weapons, and deployment of each individual Russian unit. All the information received was then promptly flowed to General Maclean, who led the British contingent of troops in Afghanistan.

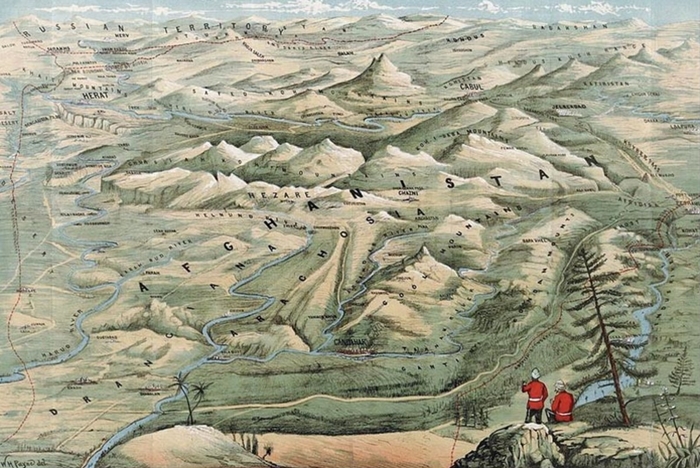

In turn, the events of 1880-1884, when the Trans-Caspian region of Russia was formed in the conquered Turkmen territories, caused particular concern among British diplomacy. The borders of the Russian Empire came close to the borders of Afghanistan. The newspaper “Novoye Vremya” described with great enthusiasm the reports of the expedition of engineer P.M. Lessar, who carried out cartographic surveys of the territories between Ashgabat and Herat, anticipating Russia’s further advance to the south.

Two Russian-English agreements of 1885 and 1887, which established the Russian-Afghan border from the Herirud River in the west to the Lesser Pamir in the east, led to the end of direct confrontation between the two powers. Great Britain received free access to Afghanistan and took control of the political life of this country, and Russia, having secured vast territories along Murghab and Kushka, focused on strengthening its political and economic positions in northern Iran and on the development of Turkestan territories and the Trans-Caspian region. In addition, on September 24, 1888, the Russian government determined a new course – the economic mastery of Khorasan, which was closely connected with the Trans-Caspian region and Herat and could be “industrially dependent” on Russia.

In such conditions, southern Iranian roads were vital for British diplomacy. But the British were unable to overcome the prohibitive position of the Russian mission in Tehran and its influence on the central apparatus of the Shah. It is no coincidence that in December 1886, the influential newspaper The Manchester Courier placed full responsibility for the financial losses of English textile manufacturers not only on the manufacturers themselves (they were accused of unwillingness to exchange colonial goods of poor quality for competitive ones), but also on British diplomats. Ambassador Sir Abbott was particularly criticized because, according to the newspaper, he was unable to defend interests in the Russian environment.

These circumstances, together with the criticism that British diplomats in the northern provinces of Iran were subjected to, forced the Foreign Office to look for ways to rapprochement with Russia. The new envoy to the Shah’s court, Sir Henry Drumond Wolfe, in the spring of 1888. After preliminary consultations with the Prime Minister, Salisbury proposed to the Russian representative N.S. Speer to conclude an Anglo-Russian agreement on the division of spheres of influence in Iran. “Russia and England,” said Wolf, “must, by virtue of this agreement, become unconditional masters in Persia.” As a gesture of “reconciliation,” the British ambassador proposed reaching an agreement on railway lines in Iran that would finally link the south of the country with Great Britain and the north with Russia.

The military culmination of the “Great Game” was an armed conflict in March 1885 near the Kushka River, called the “Battle of Tashkepri.” Victory was proclaimed when the temporary police officer Amanklych took away a horsetail [battle flag] with a horse’s tail and a crescent from an Afghan cavalryman. Then the Afghan army of about 5 thousand horsemen and infantry, as well as about 5 thousand tribal militias, suffered a complete defeat. During the battle, the Afghan troops were effectively commanded by the head of the British trainers, Lieutenant General Peter Lemsden.

August 31, 1907 In St. Petersburg, with the mediation of France, a Russian-British agreement was signed, which played a very significant role in the historical fate of the Russian Empire and Europe. This document, in essence, consolidated the shift in emphasis of Russian foreign policy from the Far Eastern and Central Asian directions towards Europe.

With the end of the “Great Game”, a new confrontation began. This time between the Triple Entente (England, Russia and France) and Germany’s alliance with Austria-Hungary. Britain was forced to move closer to Russia in the face of the strengthening of Germany, which was strengthening its positions in a number of strategic areas, primarily within South-West Africa, the Middle East and the Persian Gulf. As a prominent representative of the British ruling circles, Lord Ellenborough, said in 1903 in the House of Lords: “prefers to see Russia in Constantinople rather than a German naval arsenal on the shores of the Persian Gulf.”

Thus, history shows that major wars are preceded by very long and so-called “games”, the last of which lasted more than half a century and ended at the beginning of the last century. Less than ten years after the last treaty between Russia and Britain was concluded in 1907, the First World War was triggered.

The existing gap between the end of the First and the beginning of the Second World War in the above-mentioned context can be characterized not so much as a “game”, but as a “flirt” with the then emerging fascism. This was accompanied by the infusion of billions and billions of investments into the economy of then Germany. Even on the eve of a global catastrophe, English Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain waved the text of the Munich Agreement and declared peace had been achieved with Hitler. Soon all over Europe realized that they had fed and raised the wrong kitten.

Let us remember here the prophetic words of Winston Churchill addressed to N. Chamberlain in connection with his political and diplomatic capitulation to Germany: “You were given the choice between war and dishonor. You chose dishonor and you will have war.”

In the context of the above, it can be assumed that the principle of isomorphism, similar to the method of comparing historical analogies, also works in the field of structural analysis of international processes. Morpho-political research allows us to study the internal identities of geopolitical units that are externally similar, but separated from each other by historical time. In other words, in history there has always been irreconcilable confrontation and hostile parties. Although the difference in eras determined new enemies, the goals, essence and nature of the wars did not change. In the time dimension, one can see the coincidence of historical rhythms and a certain similarity in the algorithms for bringing complex relationships to irreconcilable contradictions, which in turn inexorably bring the hostile parties to the threshold of a global war. We see that yesterday’s allies can become sworn enemies today, and enemies can become allies.

At first glance, seemingly insignificant events or still solvable problems serve as a trigger, or as they say, a trigger for a big war. It is unlikely that Martin Luther thought about the “European” Pandora’s box in the image of the upcoming Thirty Years’ War when he nailed his 95 theses to the gates of the Castle Church of the German town of Wittenberg on October 31, 1517.

Most likely, Napoleon also planned a relatively quick but victorious operation when he launched the Italian and Egyptian expeditions. And when he was already dressed in imperial purple, old Europe was in complete disorganization. The ineffectiveness of the entrenched orders and institutions of power in European monarchies was revealed at the very first serious clash with the more modern Napoleonic France.

The fact of the murder of the heir to the Austrian throne and his wife on July 30, 1914 in Sarajevo (Bosnia) only served as a pretext for Austria to present a virtually unacceptable ultimatum to Serbia. And the cause of the First World War was acute contradictions between two military-political blocs. The Triple Alliance – Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy – arose back in 1882 and was directed primarily against Russia and France.

It is believed that Europe was also pushed towards the First World War by numerous hidden factors, the central ones being the desire of the German Empire to dominate the world, as well as the competing national interests of the major European powers.

The tragedy of the period between the two world wars was that each country turned out to be politically right, but there was no solution that was equally acceptable to all. The Versailles-Washington system of international relations collapsed. It was finally buried by the Munich Conference of 1938.

The anti-Hitler coalition of states that formed during the Second World War did not at all mean the friendship of London and Washington with Moscow, but a necessary measure to escape the fascist conquest.

Now let us think, asking ourselves the question: will the current great powers overcome their own ambitions in the face of threats common to all humanity? Is it possible that the “Great Game” of the past will now unfold in a new format throughout Eurasia? Will Kipling’s “water truce” finally come when global drought sets in?

“The possibility of global catastrophe,” warns the UN Secretary-General, “whether due to the use of nuclear weapons, climate change, disease, war or even technology spinning out of control, is real and growing. To overcome current crises and prevent future ones, humanity needs closer cooperation.”

Three decades have passed since the end of the Cold War. In the context of the above, 1991 went down in history as the year of the collapse of the USSR – the leader of the Eastern Bloc, which opposed the Western Bloc led by the United States during the Cold War. On February 1, 1992, Russian and US Presidents Boris Yeltsin and George H. W. Bush signed the Camp David Declaration. Thus, the formal and legal end of the existential confrontation between two global systems that previously had no pity for each other was announced. The first paragraph of the text of the Declaration read: “Russia and the United States do not consider each other as potential adversaries. From now on, friendship and partnership will be the hallmark of their relations…,” the next three decades still prove a certain validity of the logic of R. Kipling’s immortal phrase regarding relations between East and West.

“The modern world is on the verge of a dangerous imbalance as the United States of America is drawn into conflict with Russia and China without any clear purpose,” former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger said in a conversation with The Wall Street Journal on August 13, 2022. “We are on the brink of war with Russia and China because of problems that we have partly created, without any idea of how it will end or what it should lead to,” he said. Kissinger also questioned whether the United States could handle two adversaries at once by pitting them against each other, as happened under President Richard Nixon.

The former Secretary of State believes that there are two levels of balance. The first, which he called “absolute equilibrium,” represents “a certain balance of power with recognition of the legitimacy of sometimes opposing values.” “Because if you believe that the end result of your efforts should be the imposition of your values, then I think balance is impossible,” he said.

Another level is the recognition of limitations on the use of one’s own forces against what can destroy the balance in the world. This is what Kissinger calls a combination that requires “almost artistic skill.”

In the year of the twentieth anniversary of the end of the Cold War, the famous statesman, scientist and strategist Zbigniew Brzezinski completed and submitted for publication a new book entitled “Strategic vision: America and the crisis of global power.” ). Despite the fact that Z. Brzezinski is considered one of the ardent opponents of the former Eastern Bloc, in the introductory article of the above-mentioned book in March 2011, he seriously warned: “The modern world is characterized by interactivity. In addition, for the first time in history, the usual international conflicts paled in front of the general problem of the survival of humanity as a whole. Unfortunately, the leading powers have yet to develop joint ways to address the new growing threats to human well-being – environmental, climate, socio-economic, food and demographic. However, without relying on geopolitical stability, any attempts to achieve the necessary international cooperation are doomed to failure.”

It is unknown whether the current leaders of world politics agree with him…

CONCLUDED.

Dr. Begench Karaev deals with the problems of philosophy of law and politics. He is the author of a number of textbooks and monographs, including “Political analysis and strategic planning”, “Political analysis: problems of theory and methodology: (Experience in the study of modern Central Asian society)” and “Traditional and modern in the political life of Central Asian society (experience of political analysis)”.

///nCa, 28 November 2023

The Part One is available here:

The inevitability of dialogue about peace or futility of new “Great Game” – Part One