Dovletgeldi Khudaiberdiyev

In recent years, five bridges have been built across the Amu Darya, whose length in the territory of the Turkmenistan’s Lebap province is 830 kilometers, including three road and two rail bridges. Road and railway bridges connect Kerki town with the village of Kerkichi, and Turkmenabat with the river’s left bank. A road bridge has appeared near the town of Seydi. The importance of these bridges is enormous, in fact, a global project was carried out to revive the Great Silk Road, since their commissioning was of great importance not only for national but also international transportation.

And there are several reasons. For many years, cars were transported from one shore to the other on barges, and a motor ship plied for passengers. More than thirty years ago, a pontoon bridge was built, consisting of barges placed close to each other. Nevertheless, the capacity of these facilities did not meet the requirements of the time. Heavy-duty trucks had to stand on both banks of the river for a long time waiting for their turn to pass. Now freight and passenger transport runs non-stop on three capital bridges at a speed corresponding to the rules of the road. And trains used to run on the only railway bridge, which served exactly 116 years until the new one was commissioned.

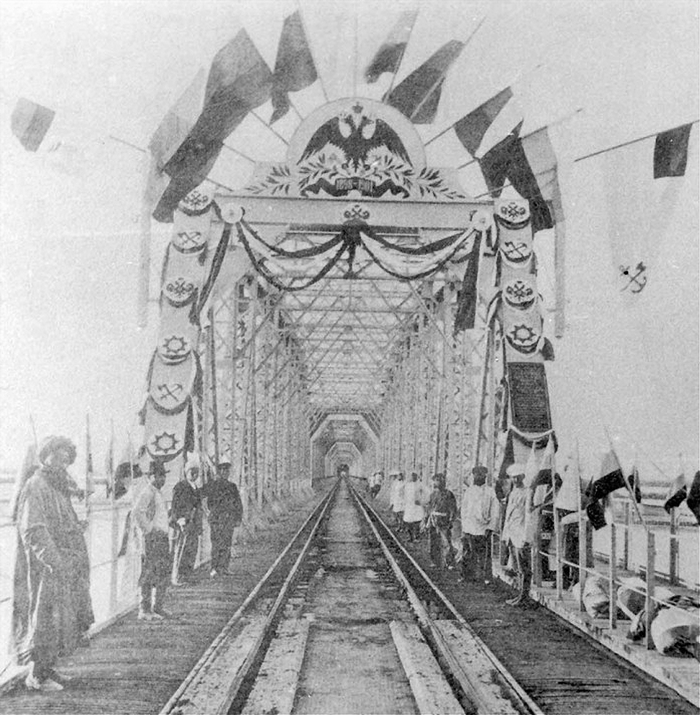

This magnificent bridge still inspires awe. It feels like it holds the accumulated spirit of all those who brought it to life: the visionary engineers, the tireless workers, and the determined soldiers. Sailing beneath it, you feel like a tiny boat passing under a slumbering giant. From afar, its silhouette stretches across the horizon, a gleaming silver arrow piercing the distance.

At the dawn of the 20th century, it claimed the title of the world’s longest river bridge. It replaced a fragile wooden predecessor, that served for just 14 years. That bridge, a patchwork of four independent crossings linked by a precarious dam system, was described by famed explorer N.M. Przhevalsky: “There is a bridge over the Amu Darya, which, however, cracks, but nevertheless the train passes safely…”

Though short-lived, the old bridge bore the brunt of the Amu Darya’s unyielding temper. Every flood season tore away at its planks, demanding urgent repairs.

Huge sums were spent on its maintenance, which gave rise to many rumors. Old-timers said that the engineer built a metal bridge on stone pillars at his own risk, spending on it one annual state subsidy for the maintenance of a wooden bridge in order to save the state treasury from heavy costs in the future. And this rumor is far from the truth. The construction of the new railway bridge was carefully designed, planned and coordinated at all levels. A special construction department was established in Chardjui (that was the name of the city of Turkmenabat at that time), which was headed by an experienced railway engineer Stanislav-Kostka-Marian Olshevsky.

The construction of the bridge is connected with another outstanding name – the bridge builder Professor Nikolai Belolyubsky, who arrived in Chardjui in 1895 and got acquainted in detail with the geographical and hydrographic features of the river. A commission established in St. Petersburg had offered him two options for a bridge: build the bridge forty versts upstream or fifteen versts downstream from the city.

But Belolyubsky saw the flaws in both proposals. Both would require laying tracks far from bustling settlements, pushing up costs to exorbitant levels. Instead, he chose a seemingly unconventional location: right next to the existing wooden bridge, where an ancient ferry had faithfully served travelers for centuries. Time proved Belolyubsky’s genius.

Though preparations began in 1895, the construction commenced on October 17, 1898. On that day, the builders, armed with grit and determination, entered a grueling battle against the mighty Amu Darya.

Construction materials were delivered from different cities. Factories in Bryansk, Mariupol and Warsaw supplied metal structures, high–quality cement was supplied from Volsk, rubble stone and marble limestone were supplied from Samarkand, and shore protection materials were produced Tejen. Millions of rivets were needed to connect the bridge structures together.

Now most of the bridge runs overland. Three large ones – the Karakum River, Karshinsky, Bukharsky – and dozens of small channels take away a significant part of the water of the once crazy river (although even now it sometimes shows its character), and against the background of a two–kilometer structure, it does not seem as formidable as historians described it, as our parents remembered it several decades ago. And then the river showed the builders its temper. Considerable effort and skill required the construction of supports and the collection of spans. Take the incident in late 1900: an ice drift tore through the scaffolding for one span, sending 88 tons of metal plummeting into the icy depths. But the spirit of the builders couldn’t be drowned. Bryansk’s metallurgists swiftly forged replacements, ensuring new structures were in place before the 1901 floods. This unwavering determination allowed the bridge to be opened to traffic by May of the same year.

The official opening was held on 27 May 1901. Ten steam locomotives thundering across its steel spine sent a roar of defiance against the once-raging Amu Darya. Then, a special train carrying dignitaries and spectators traversed the bridge.

Nothing has power over time. The hour has come when this bridge became the property of history. It remained the first bridge connecting the two banks of the Amu Darya with its wayward current. And the calculation of the designers turned out to be so accurate, the work of the builders was so solid that it did not succumb to floods or ice floes. Naturally, all this time the bridge was carefully maintained. In 1957, major repairs were carried out and the bridge supports were reinforced with cement.

It would be possible to put an end to this story. However, there is a need to draw the reader’s attention to one circumstance. The river, perpetually reshaping its course, has consistently aimed its flow towards the bridge, carving a passage between its pillars throughout its life. Even today, its waters dance under three bridges, the old one standing defiantly alongside its modern successors. ///Neutral Turkmenistan newspaper, 20 December 2023