Begench Karaev

Let’s go back to the then Kabul …. When a limited contingent of Soviet troops entered Afghanistan at the end of December 1979, Brzezinski’s main task was solved. The USSR received a conflict that was supposed to rapidly absorb seemingly unlimited resources. At the same time, the US costs for maintaining and expanding the Afghan resistance were relatively skimpy – and those were mainly shifted to Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. Moreover, even Iran, hostile to the United States, joined the process in this situation, supporting the struggle of the Hazara Shiites against the pro-Soviet Kabul regime.

As S. Berdiniyazov tells his students today, although the collection of information and analytics, which became the main direction of his duties in the first years of his diplomatic activity, effective work required much more. Therefore, I had to spend hours studying the history of the region in detail, the theory and applied aspects of geopolitics, the development of civilization, culture and trade, etc. Of no less importance was the study of many aspects of the foreign policy of both the United States and other leading Western states.

Sometimes you wonder if young Sapar ever thought about the ups and downs of diplomacy when he received a diploma of a purely peaceful profession from the Faculty of Foreign Languages of the TSU named after M. Gorky (now named after Makhtumkuli) with a degree in philology, and teacher of English. Although he aspired to return to his native village in the southern outback of Turkmenistan after Alma mater, his passion for research work for the whole 12 years connected him with scientific activities in the Central Asian Joint Directorate of the Luch Research Institute. Thus, S. Berdyniyazov entered the diplomatic field at a relatively mature age – at the age of 36 and was immediately assigned to Pakistan.

The events in Pakistan in the 70s did not leave S. Berdyniyazov indifferent during his diplomatic service in Afghanistan, which fell on the most difficult period, not only in the Union, but also in the region, and in the world as a whole. If the USSR of the détente period was characterized as a time of “stagnation”, ten years later, that is, the mid-80s entered the history of the Soviet people as the beginning of “unbridled democracy and glasnost.” The later advent of democracy on Soviet soil and its peculiar “celebration” continued only until the collapse of the power system with global consequences occurred.

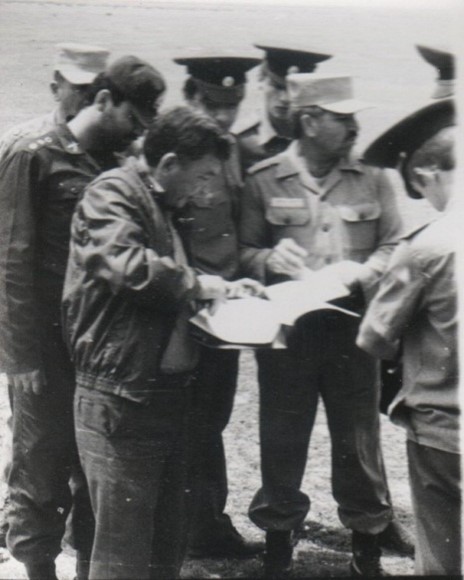

The author of these lines, in those years, while still a young guy who was just over 30 years old, on one of his business trips in the year of the Seoul Olympics-88, involuntarily became a direct witness to a telephone conversation between the then governor of the Herat province, Fazal Haq Khalikyar, and a certain representative of the Soviet embassy in Kabul. Judging by the calm tone of the governor’s conversation, one could guess that he was talking to an experienced specialist with excellent knowledge of Pashto and Urdu. The reason for this dialogue, which was distinguished by the lack of an orderly tone from the other end of the wire, characteristic of many Soviet-party instructors sent to Afghanistan, was a scandal between two warring groups of the local population.

To use the jargon of the post-Soviet chaps of the 90s, the “strelka” was identified and was immediately packed right on the site where humanitarian flour was distributed according to the queue list, where local residents impatiently waited, holding shabby bags of compact size in their hands, on most of which the inscriptions clearly appeared advertising type: “USAID to the Afghan people”. It was paradoxical that several handfuls of flour were poured into them from standard 50-kilogram bags with sewn-in paper tags “Stavropol flour – 1st grade”. It became clear that here, too, another unforgivable blunder of Soviet propaganda was made, as a result of which the Eastern people thanked the invisible Americans for food support. In fact, this specific humanitarian aid then came from the Shuravi from the other side of the northern border of Afghan territory through the Turgundi railway station and was delivered to Herat through dangerous mountain serpentines.

Hotheads in turbans at first shouted hoarsely among themselves, and then, apparently not resolving the dispute in a “diplomatic” way, took up positions against each other at a distance of 40 meters, while leaning on sacks of Stavropol flour. Suddenly, on command, the shutters of the popular “Kalash” slammed shut, or how often they called “Kalaks” in the local dialect, and there were literally seconds left before the mutual command “Fire!”. It was like a group duel according to the Pashtunwali laws, which are fundamentally different from the rules for protecting the honor and dignity of the European court nobility. By the way, veterans of the war in Afghanistan remember: in that military campaign there were no weapons more reliable than AK. This was understood by the Mujahideen, who de facto, that is, in battle, did not use any other small arms except the Kalashnikov assault rifle. Although they had deliveries from the United States, and from Italy, and from other states. Another surprising fact is that in those years, hundreds, maybe thousands of Afghan babies born in different parts of the country were named “Kalash” – in honor of the unsurpassed work of the legendary Soviet weapons designer Mikhail Timofeevich Kalashnikov.

How can one not recall one of the most popular running jokes from the Soviet past. In short, when a baby was born in the family, and there was no way to buy baby carriages, because there was a shortage in the country, the wife asked her husband, who works at a metal plant:

– Vasya, you are so honest, you never dragged anything from the factory, but here it’s quite a disaster: there’s no way to get strollers. Bring parts from the factory, assemble a stroller for your son, just once!

The husband struggled with his honesty for a long time, but he became unbearably sorry for the child and his wife, and he stole parts from the factory, brought them home, began to design, but after a while he said to his wife with irritation:

– Mash, nothing comes of it: no matter how much I collect a baby carriage, I still get a Kalashnikov assault rifle!

So, at that very critical moment, there was no time for anecdotes. One of the civilian representatives, apparently well acquainted with local customs and the consequences of their violation, in broken English turned to your obedient servant, dumbfounded then by what had happened, demanding an urgent connection with the Secretary General of the Soviet Union himself. Literally, he declared, or rather conveyed with a majestic air, the following ultimatum: “You, Shuravi, distributed flour here specifically in such a way as to cause discord among us – peaceful Afghan residents! I demand immediate communication with your Tsar!”. I realized that he demanded an immediate audience with the USSR Secretary General M. Gorbachev himself, who in the perestroika common people was sometimes called almost in an oriental way: “Mikhail the Marked.” Well, what could be answered here, except as a request to prevent bloodshed, because there is a lot of flour and enough for everyone. At the governor’s office, where we arrived together with the bearer of the “ultimatum”, we already knew. There, in the reception room, we learned that they had decided to hastily contact the USSR Embassy in Kabul. The door of the governor’s office remained ajar and the alarmed voice of Fazal Haq Halikyar partially reached us, that is, the “parliamentarians” waiting in the reception room.

As it became known, many years later, the person with whom the governor of Herat spoke on the phone turned out to be one of the senior Soviet diplomats, Sapar Berdyniyazov, who was aware of the life of the then Afghan society in detail. In addition, Sapar Komekovich knew the subtleties of the psychology of the Afghans, and therefore he was able to skillfully settle this kind of “showdown” that happened almost daily. Here, somewhat ahead of events, we add that Halikyar, being known as a well-educated, wise, intelligent, broad-visioned person, two years after this incident became the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of Afghanistan. By that time, a year had already passed since Sapar Berdyniyazov left Kabul, completing his diplomatic mission.

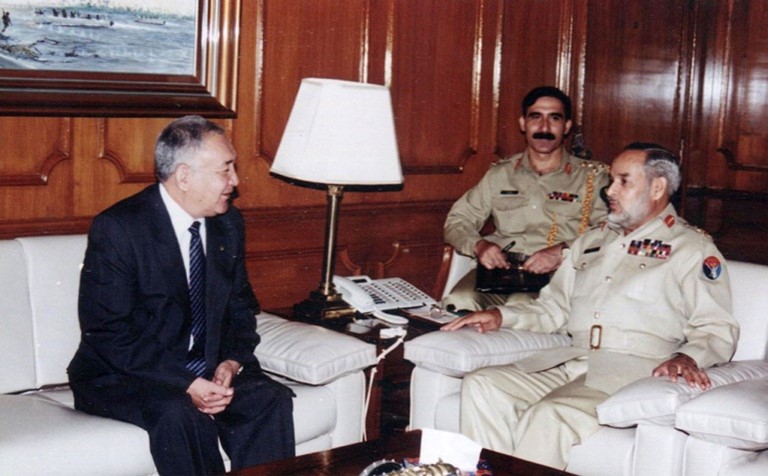

The value of Sapar Berdyniyazov and the “respect” shown to him in the Afghan embassy of the Soviet Union was largely due to the fact that he knew Pakistan well and had trusting ties in this country, established thanks to the respect that he earned during his work in Karachi and Islamabad. And the Pakistani side, as is known, almost from the very beginning of the “Afghan campaign” of the Soviet Union was involved in the organization of the Mujahideen movement under the guidance of CIA instructors.

About the author: Begench Saparovich Karaev, defended his doctorate in philosophy in April 1996 in Moscow, published several monographs and dozens of articles on the theory and methodology of political analysis, including in relation to the conditions of the traditional Central Asian society. Starting from 1997, over the next almost a decade and a half, he headed the information and analytical structure of the Foreign Ministry of Turkmenistan. From April 2004 to February 2005, he conducted research and lectures at Indiana University Bloomington (Indiana University Bloomington) as part of the targeted program Fulbright for Visiting Scholars (USA). Currently, he is a senior lecturer at the IIR of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Turkmenistan.

To be continued . . .

///nCa, 28 December 2022